Go-Far 2018

Graphics by: Vanessa Goh

In Soviet-era public housing, poverty haunts the elderly

Low pensions, no savings and kids who don’t help have pushed many elderly people in Tallinn below the poverty line, experts say

By Dewey Sim

Photo by: Esna Ong

With a basket of white and yellow daisies in his hand, 83-year-old Vladimez Pisazoce hobbles to the centre of Pae Market, a makeshift farmers’ market located in central Tallinn.

The retired mechanic then spends the entire day trimming these homegrown flowers and arranging them in small, coloured containers for sale.

“When our flowers blossom, we will bring them down to the market and sell. But on some days, we don’t earn a single cent,” said Mr Pisazoce, whose wife accompanies him at work.

The couple have seven children but has had to work beyond the retirement age of 65 to make ends meet, as their children do not contribute financially.

“Our children have their own families and they are trying to survive on their own. They wouldn’t be able to help us,” said Mr Pisazoce.

This lack of financial support from children, a low national pension and lack of savings are reasons why many elderly people in Tallinn live in poverty, experts said.

Many of the elderly also struggle with rising rent, and are unable to find new jobs as they do not speak Estonian, they added.

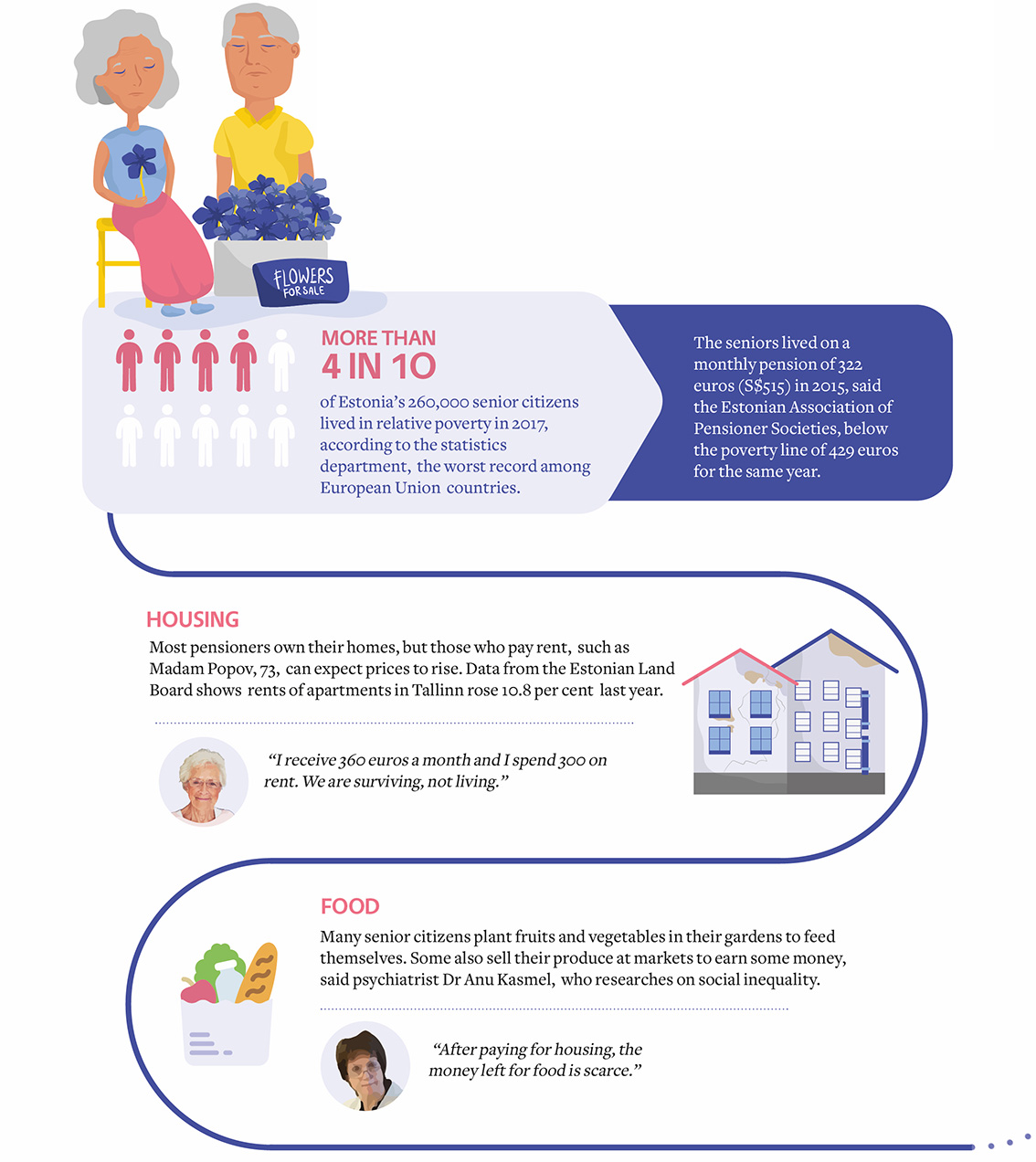

More than four in 10 of Estonia’s 260,000 senior citizens lived in relative poverty last year, according to the country’s statistics department, in what was the worst record among European Union (EU) countries.

These senior citizens survived on a monthly pension of about 322 euros (S$515) in 2015, said the Estonian Association of Pensioner Societies, below the poverty line of 429 euros for the same year.

Caged In

Photo by: Esna Ong

A large number of the capital’s senior citizens, like Mr Pisazoce, live in Soviet-era social housing areas in Mustamäe, Lasnamäe and Kopli. These areas, which were first developed to solve a housing deficit after World War II, are commonly known as “bedroom communities”, and are small in size.

According to a study by the University of Tartu, the average living space per person in these areas was 11.8 square metres — Singaporeans enjoy an average of 24 square metres of living space each.

Many of these unmaintained housing estates are no longer fit to live in and perpetuate poverty among the elderly, said Ms Johanna Holvandus, a human geography researcher at the university.

The elderly there are isolated and do not interact with the surrounding areas, added Ms Holvandus. “The housing areas create a sense of anonymity. There are no opportunities. Everybody is caged in.”

While most pensioners own their homes, others who pay rent may soon have no roofs above their heads. Data from the Estonian Land Board and the country’s statistics department showed that prices and rent of apartments in Tallinn rose by 7.5 and 10.8 per cent respectively from last year.

This phenomenon is due to housing rents rising faster than pensions, said psychiatrist Anu Kasmel, who researches social inequality in Estonia.

“After paying for housing, the money left for food is scarce. This is the reason why many of them continue to work or have their own vegetable gardens to get additional food,” added Dr Kasmel.

Mr Daniel Coll, a losing candidate in Lasnamäe’s municipal election last year, said that language is another big factor why the monolingual Russian-speaking senior citizens cannot find jobs.

In Tallinn, 50.1 per cent of Estonians speak Estonian as their native language, while 46.7 per cent, most of whom are senior citizens of Russian ethnicity, speak Russian, 2012 statistics showed.

“It is already very difficult to get work here if you don’t speak English. And it’s even tougher when they don’t speak both English and Estonian,” added Mr Coll, who now heads the content department of a gaming company.

Proficiency in the Estonian language increases one’s chances of employment in Estonia, said Ms Õie Jõgiste, an adviser at the employment department of Estonia’s Ministry of Social Affairs.

Ms Jõgiste added that there are language clubs and chat rooms available for the elderly to pick up Estonian.

Left Alone

Photo by: Esna Ong

Weakening family relations, together with elderly’s individualistic attitudes, also nudge them below the poverty line as they receive little to no support from their children, said Ms Luule Sakkeus, who heads the population studies department at Tallinn University.

“When children grow up, especially when they go on to higher education, they usually leave the parental house and start living on their own,” she said, adding that senior citizens are often left to support themselves financially.

The lack of government planning after Estonia gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 also contributed to the elderly’s current plight, said Tallinn mayor Taavi Aas.

“Our government has (been) prioritising fast growth of (our) economy and low taxes over social security,” he said.

In addition, retirees have spent most of their lives under the Soviet occupation and they had no opportunity to save money or resources for their elderly years, added Mr Aas.

Uphill Battle

Photo by: Esna Ong

The Estonian government, aware of the elderly’s plight, has started rolling out measures to ensure that the elderly stay out of poverty.

Last year, the Baltic state adopted a flexible pension system that allows senior citizens to receive pension while working concurrently.

In addition, the Tallinn City Government raised pension by 7.6 per cent and provided pensioner discounts for food and events in April this year.

The Ministry of Social Affairs has also implemented several long-term frameworks such as the Welfare Development Plan to promote equal opportunities for elderly employment.

Despite these changes, Mr Zsolt Bugarszki, a social policy lecturer at Tallinn University, said that Estonia’s senior citizens would still face difficulties finding jobs as they are unskilled.

“Most of the people who are retired today in Estonia were low-skilled factory workers and people working in agriculture. They did not learn entrepreneurial skills in school or from life experiences,” he said.

For many elderly in Tallinn, there is little to cheer about as uncertainty looms. “I just hope there will be more help provided for elderly to get food and household products,” said 76-year-old pensioner Yulia Ilina.

“For us, we just look forward to our birthdays. We get 100 euros more as a gift.”